Natural History Museum: an institution for everyone

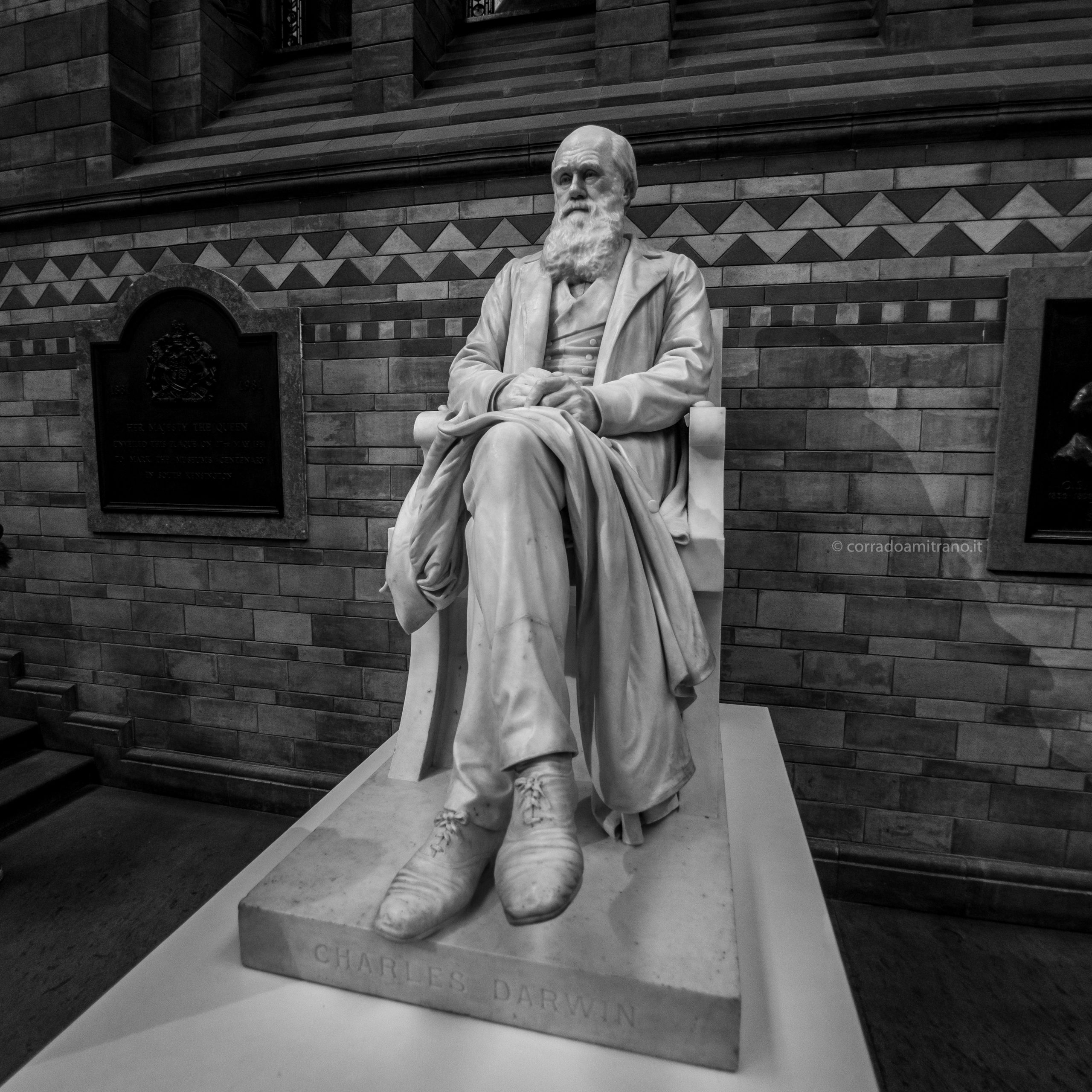

The palaeontologist Richard Owen, appointed Superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum in 1856. His changes led Bill Bryson to write that “by making the Natural History Museum an institution for everyone, Owen transformed our expectations of what museums are for”.

Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited. Land in South Kensington was purchased, and in 1864 a competition was held to design the new museum. The winning entry was submitted by the civil engineer Captain Francis Fowke, who died shortly afterwards.

The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent. The original plans included wings on either side of the main building, but these plans were soon abandoned for budgetary reasons. The space these would have occupied are now taken by the Earth Galleries and Darwin Centre.

Work began in 1873 and was completed in 1880. The new museum opened in 1881, although the move from the old museum was not fully completed until 1883.

Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of Victorian London, manufactured by the Tamworth-based company of Gibbs and Canning Limited. The tiles and bricks feature many relief sculptures of flora and fauna, with living and extinct species featured within the west and east wings respectively. This explicit separation was at the request of Owen, and has been seen as a statement of his contemporary rebuttal of Darwin’s attempt to link present species with past through the theory of natural selection.

The central axis of the museum is aligned with the tower of Imperial College London (formerly the Imperial Institute) and the Royal Albert Hall and Albert Memorial further north. These all form part of the complex known colloquially as Albertopolis.